But while I pondered I had unconsciously, in my listlessness, in my desperation, been drawing a picture where I should, like my neighbour, have been writing a conclusion. I had been drawing a face, a figure. It was the face and the figure of Professor von X. Engaged in writing his monumental work entitled The Mental, Moral, and Physical Inferiority of the Female Sex. […] Drawing pictures was an idle way of finishing an unprofitable morning's work. Yet it is in our idleness, in our dreams, that the submerged truth sometimes comes to the top. A very elementary exercise in psychology, not to be dignified by the name of psycho-analysis, showed me, on looking at my notebook, that the sketch of the angry professor had been made in anger. Anger had snatched my pencil while I dreamt. But what was anger doing there? Interest, confusion, amusement, boredom – all these emotions I could trace and name as they succeeded each other throughout the morning. Had anger, the black snake, been lurking among them? Yes, said the sketch, anger had. It referred me unmistakably to the one book, to the one phrase, which had roused the demon; it was the professor's statement about the mental, moral and physical inferiority of women. My heart had leapt. My cheeks had burnt. I had flushed with anger. There was nothing specially remarkable, however foolish, in that. One does not like to be told that one is naturally the inferior of a little man – looked at the student next me – who breathes hard, wears a ready-made tie, and has not shaved this fortnight. One has certain foolish vanities. It is only human nature, I reflected, and began drawing cartwheels and circles over the angry professor's face till he looked like a burning bush or a flaming comet anyhow, an apparition without human semblance or significance. The professor was nothing now but a faggot burning on the top of Hampstead Heath. Soon my own anger was explained and done with; but curiosity remained. How explain the anger of the professors? Why were they angry? For when it came to analysing the impression left by these books there was always an element of heat. This heat took many forms; it showed itself in satire, in sentiment, in curiosity, in reprobation. But there was another element which was often present and could not immediately be identified. Anger, I called it. But it was anger that had gone underground and mixed itself with all kinds of other emotions. To judge from its odd effects, it was anger disguised and complex, not anger simple and open. – Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, 1929

A Room of One’s Own is an essay published in 1929 by the English writer Virginia Woolf. Considered a classic of the women’s movement, Woolf’s essay explores the social and material conditions necessary for women to create literature. Within the context of the early 20th century, Woolf argues that women need both financial independence and a room of their own to fully develop their creative potential. This ‘room’ becomes a metaphor for private property, material and intellectual independence, personal privacy, the right to cultural production, and a distinct discursive space in the writing of history.

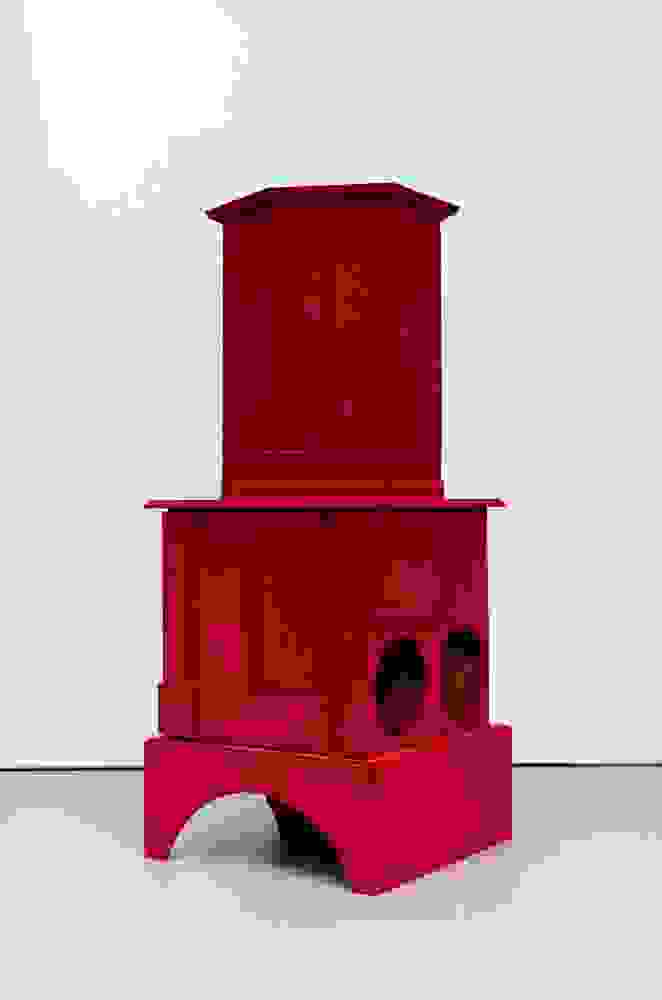

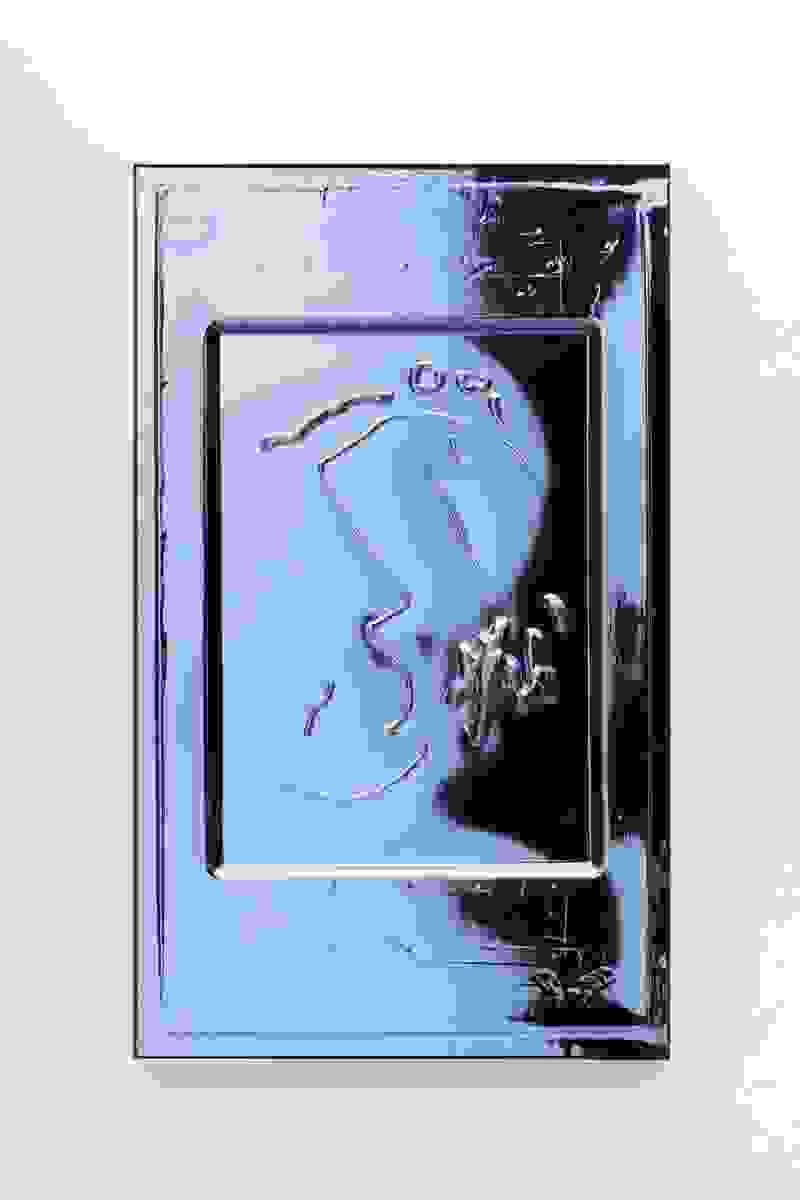

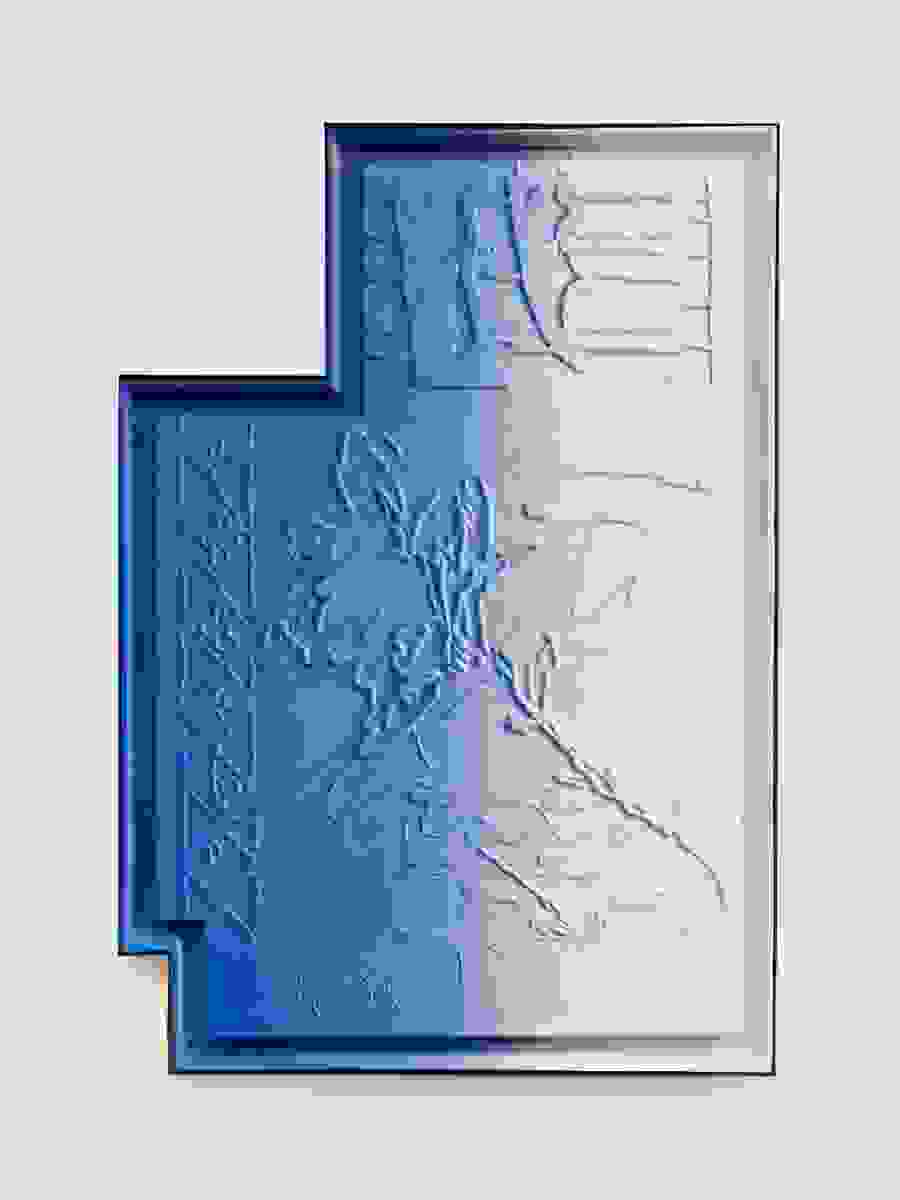

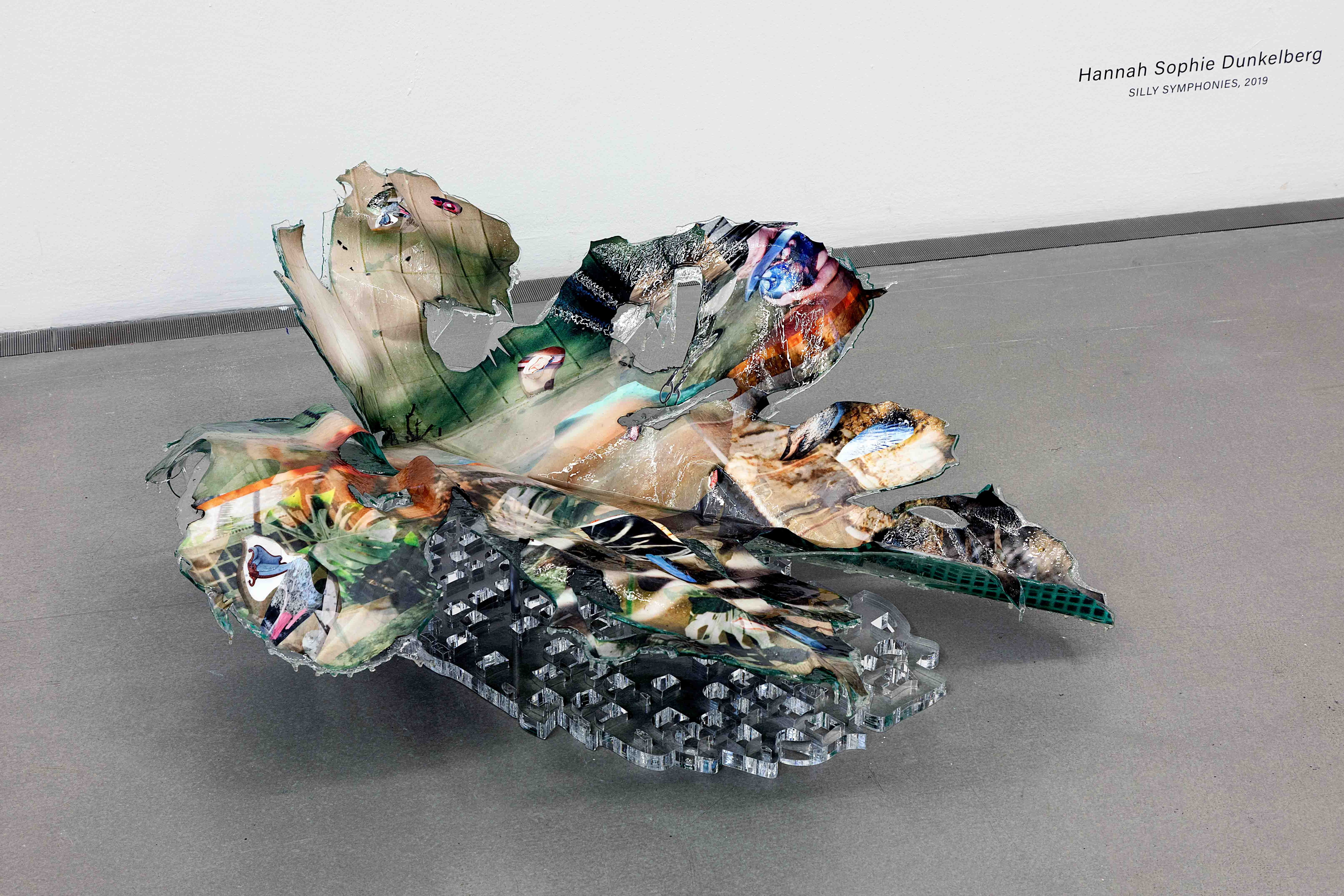

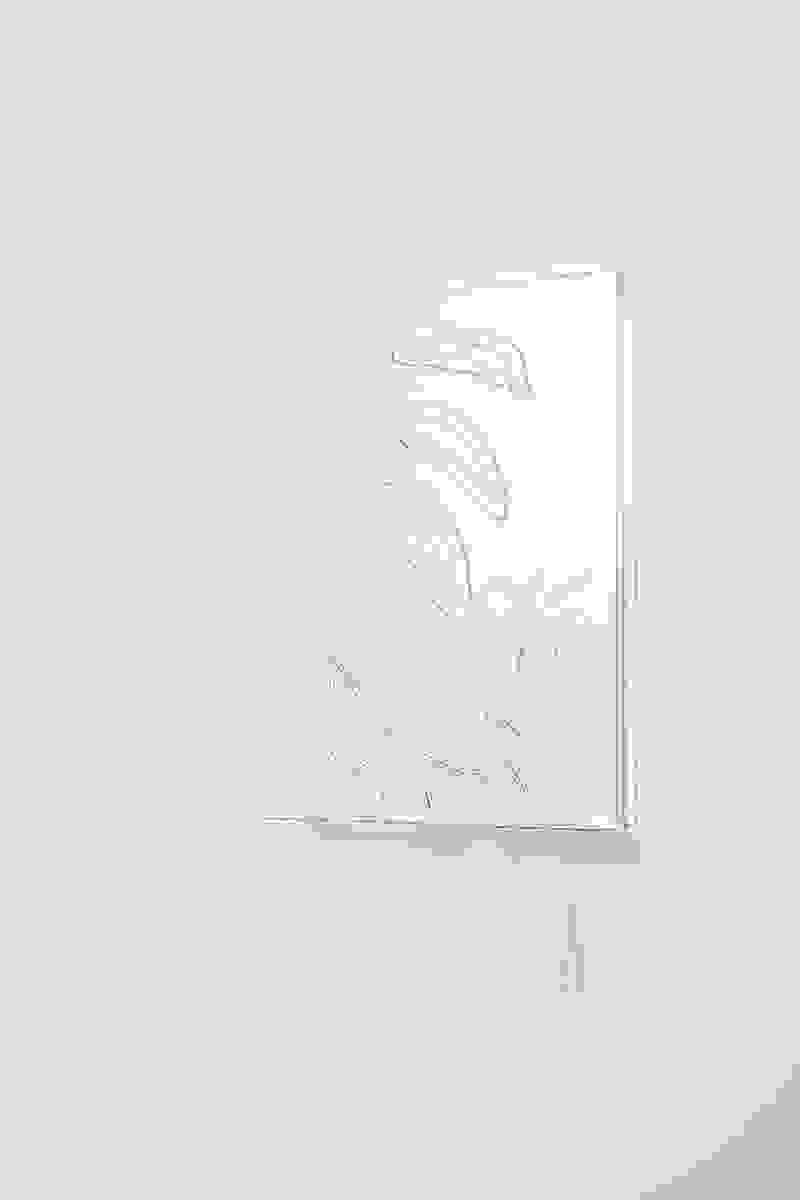

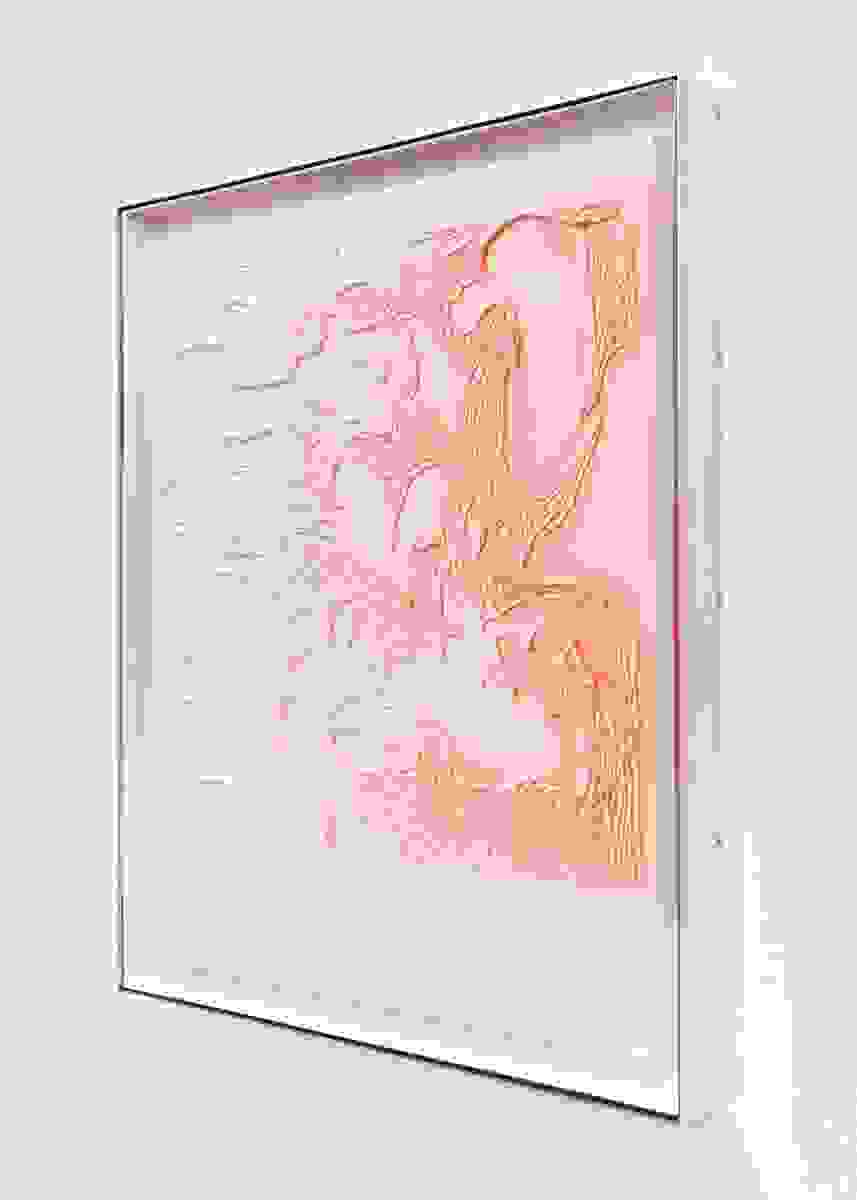

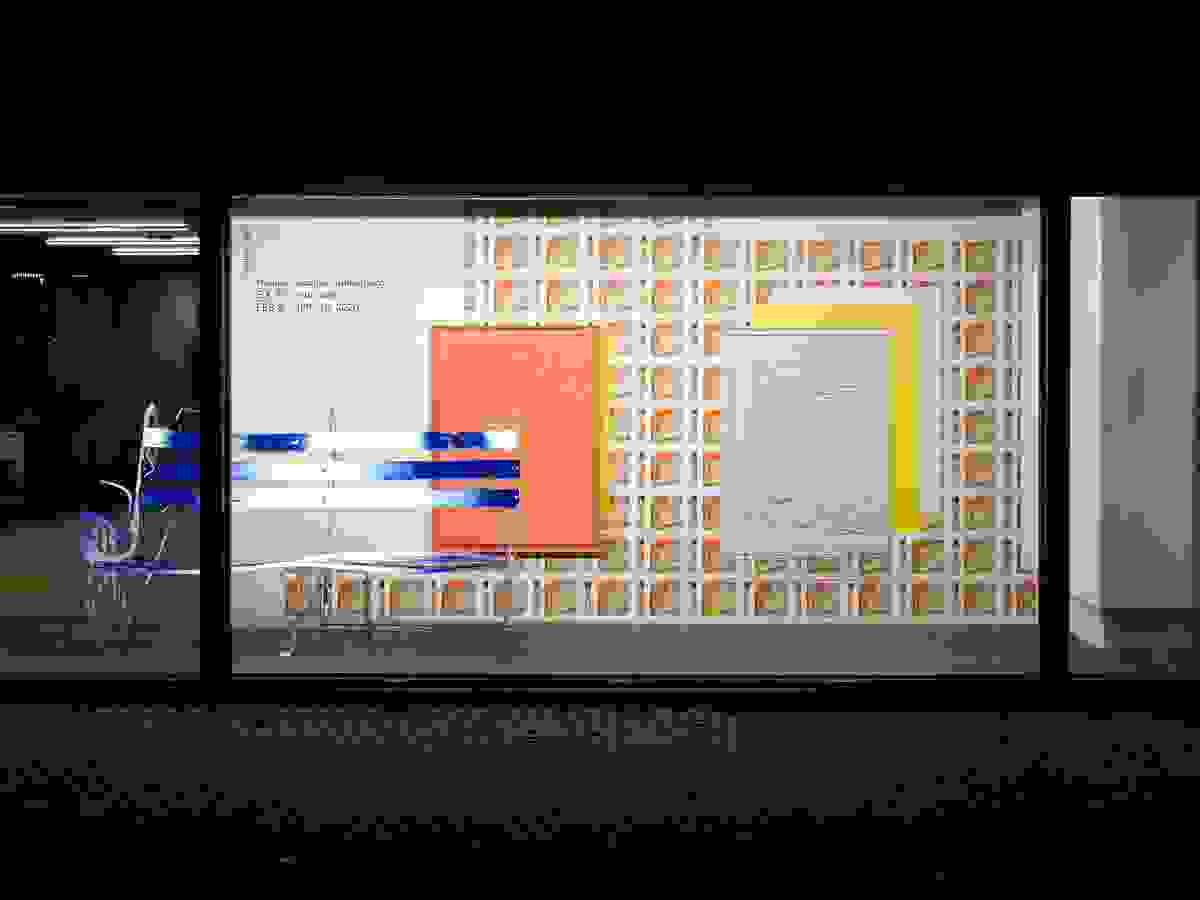

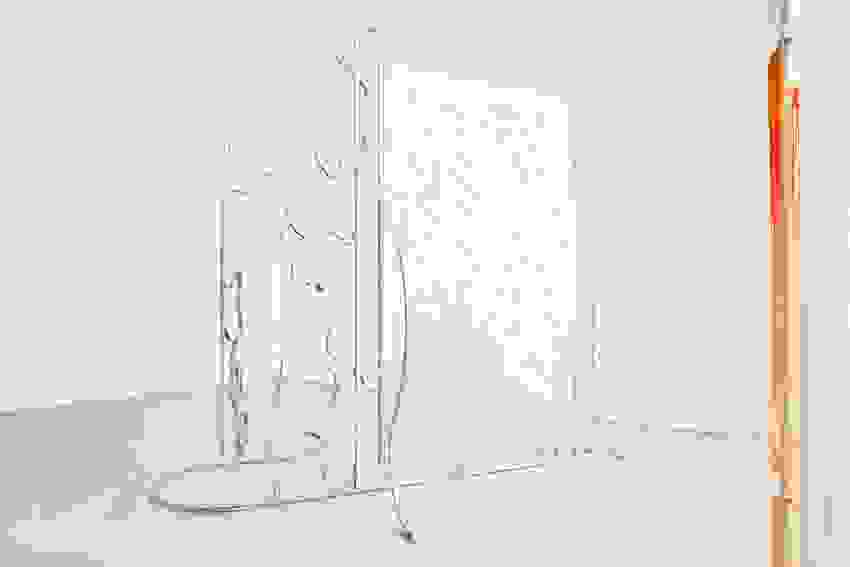

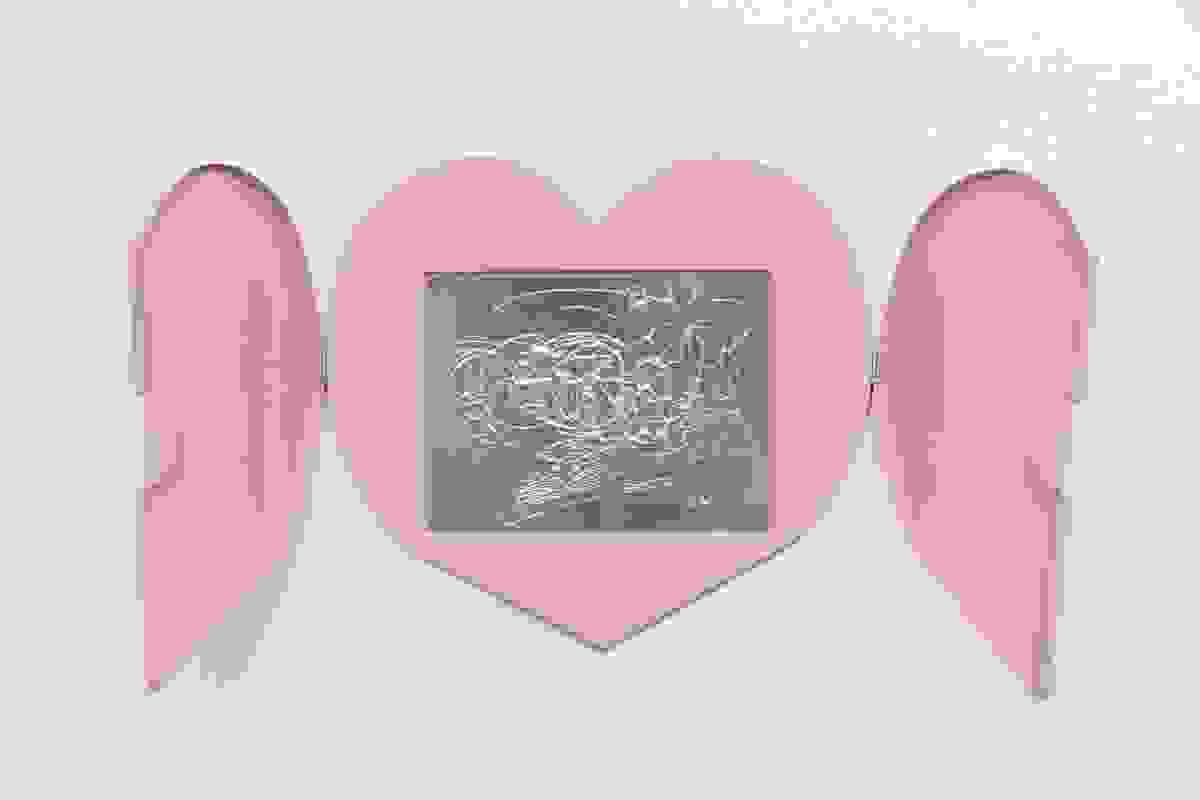

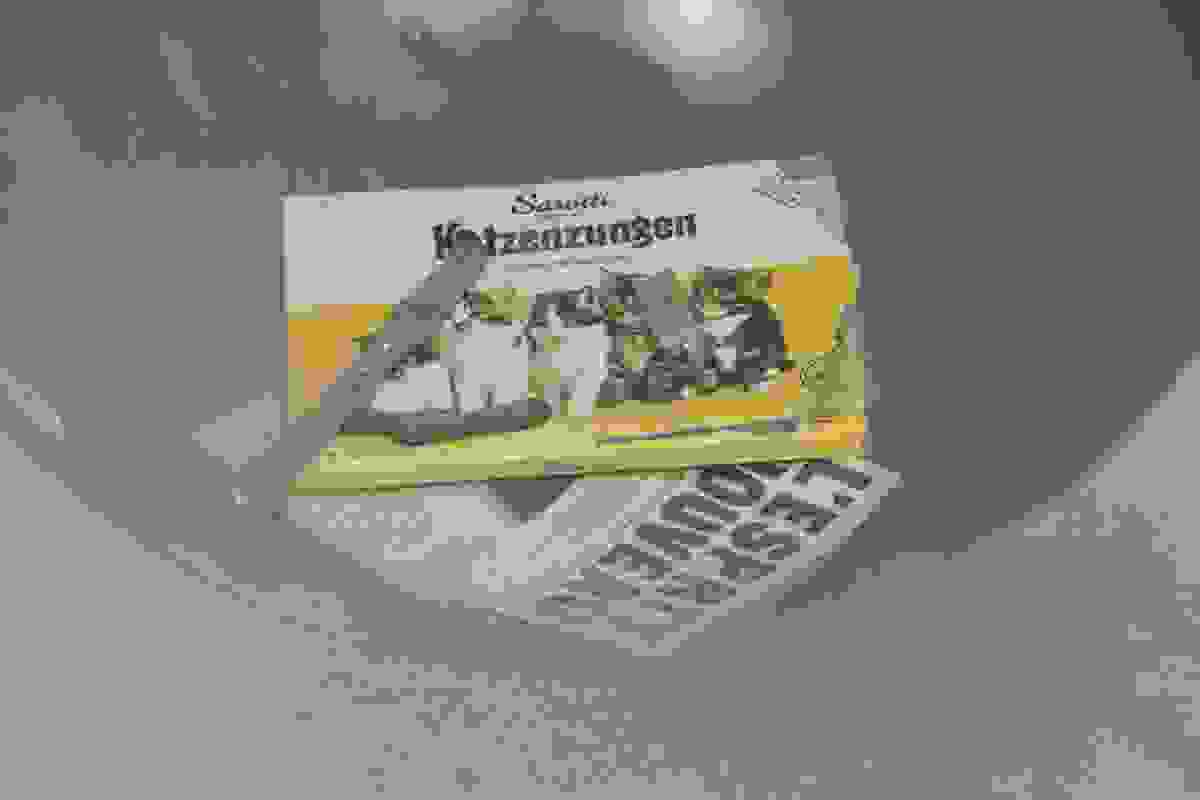

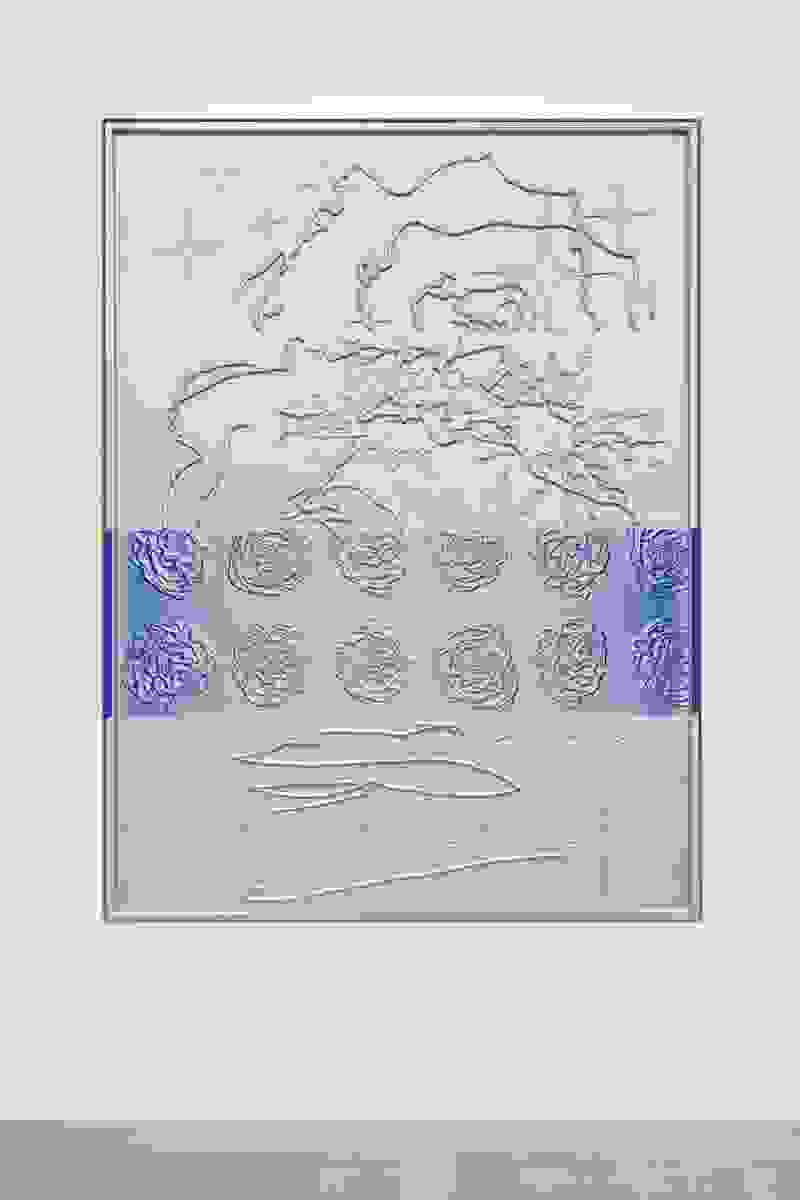

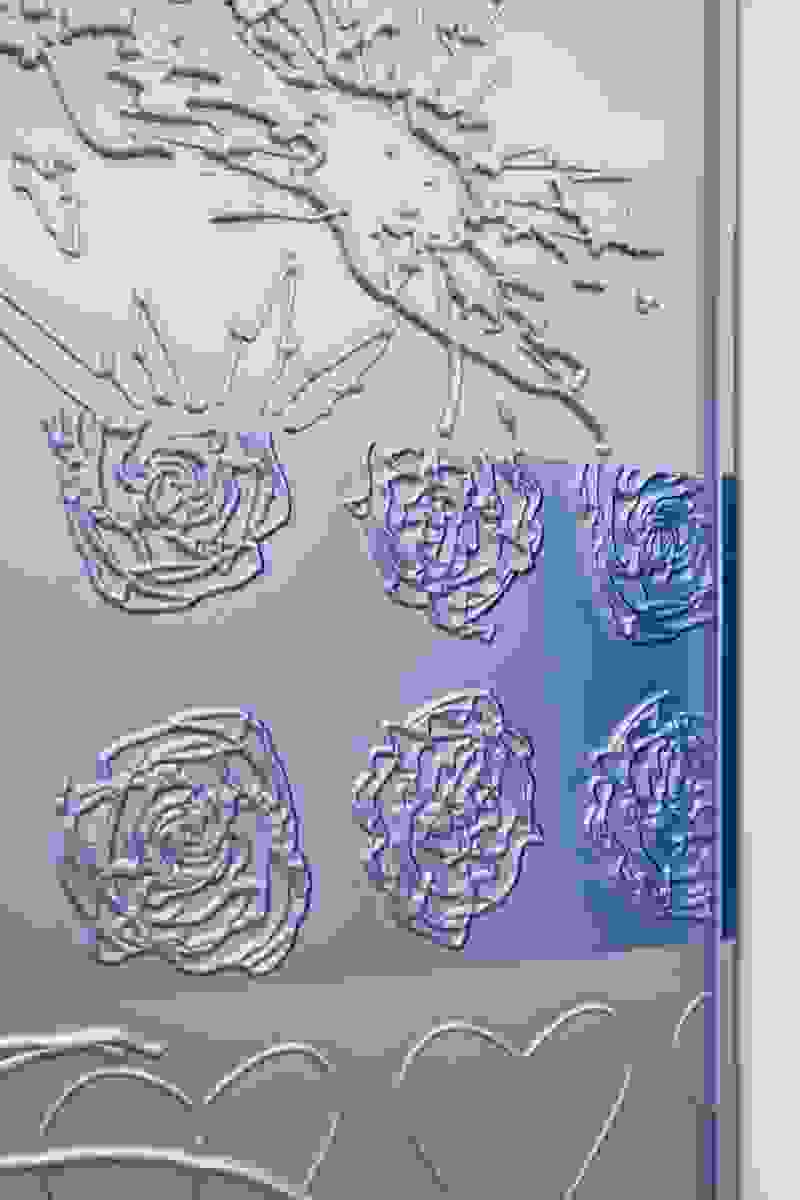

In her solo exhibition, a room of my own, at Mehdi Chouakri Berlin, Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg takes up Woolf’s literary form of social critique; she transfers the writer’s plea to reevaluate the connections between gender, autonomy, and art into her own sculptural discourse. The exhibition opens with Dunkelberg’s own interpretation of the drawing mentioned in the quote, which Woolf’s fictional writer creates impulsively out of an affective response of anger – of Professor von X, a figure easily read as an analytical objectification of the institution of patriarchy. Stored in a pink heart-shaped cabinet and translated into the drawing process the artist has developed, where a delicate hand drawing is gradually abstracted and subjected to a mechanical process, a dialogue unfolds not only about female-associated artistic practices, techniques, and media but also the nuanced attribution of meaning and stereotyping of male and female anger – and more generally, emotionality.

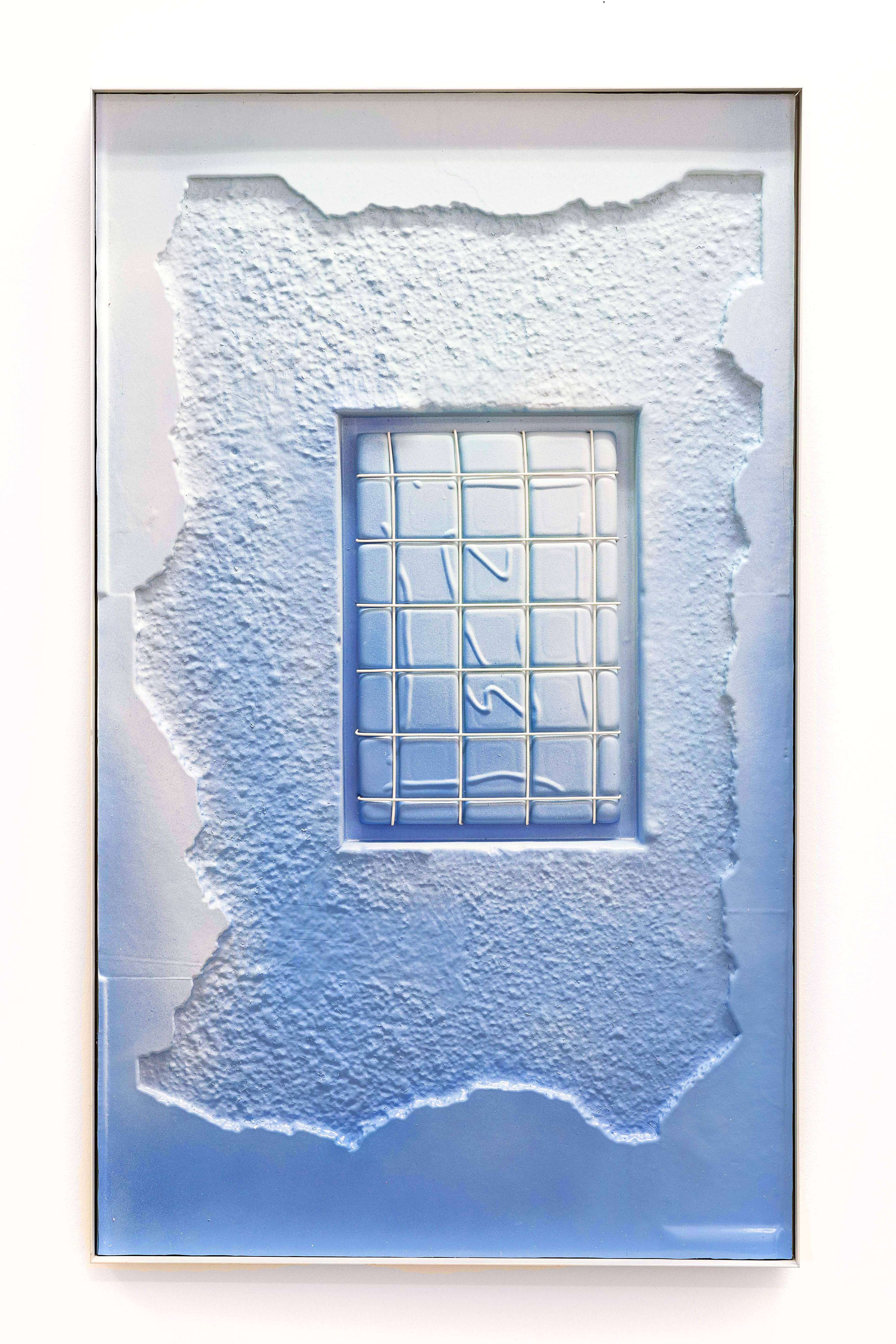

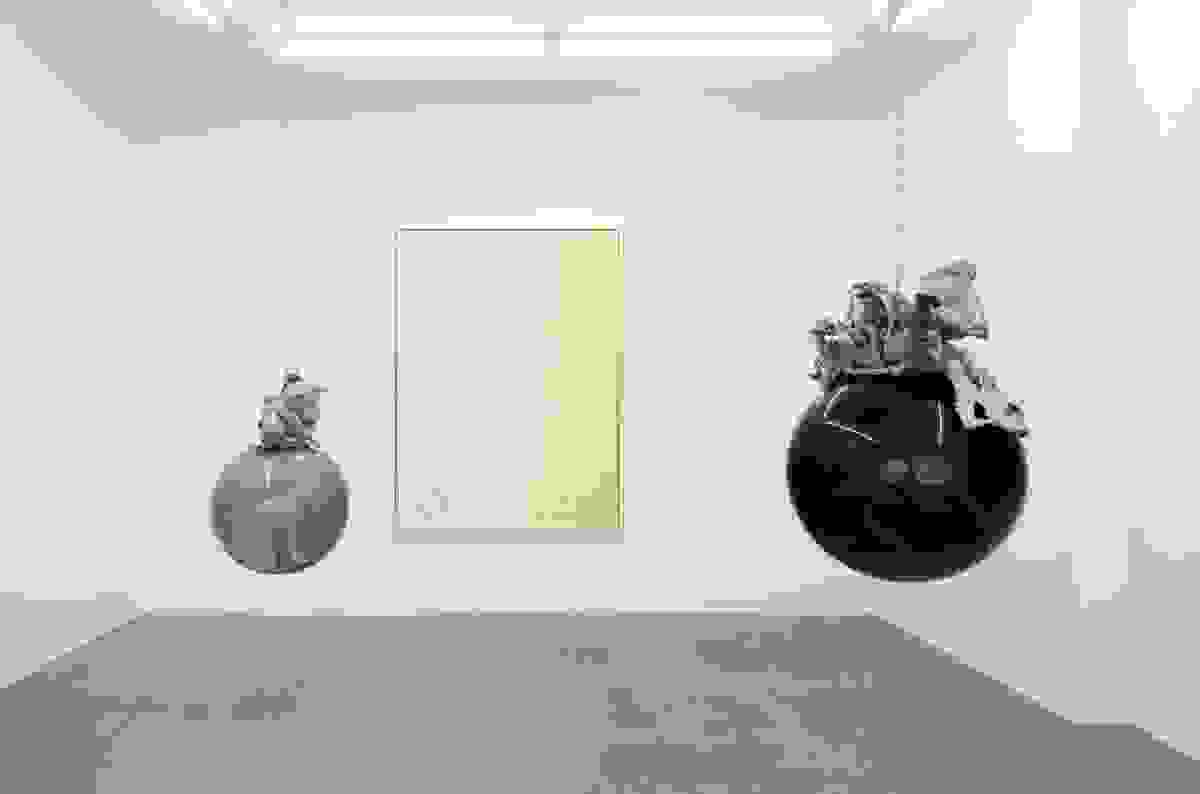

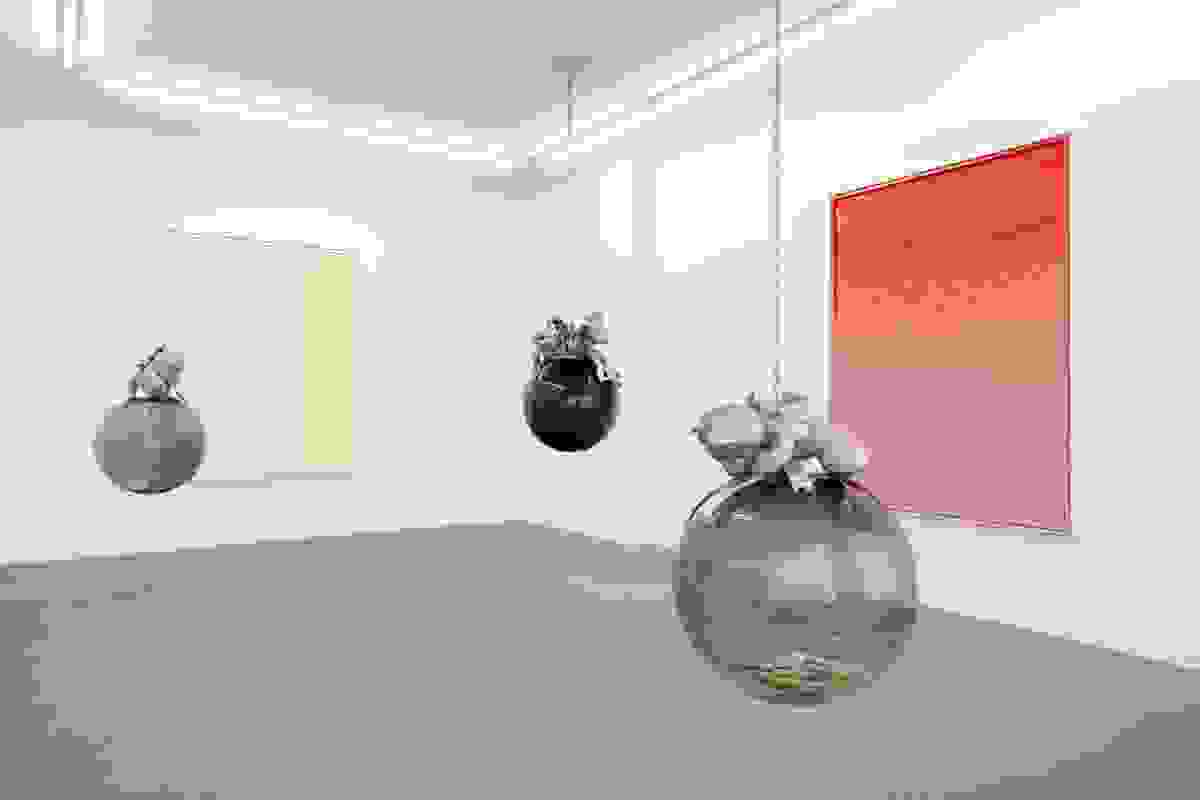

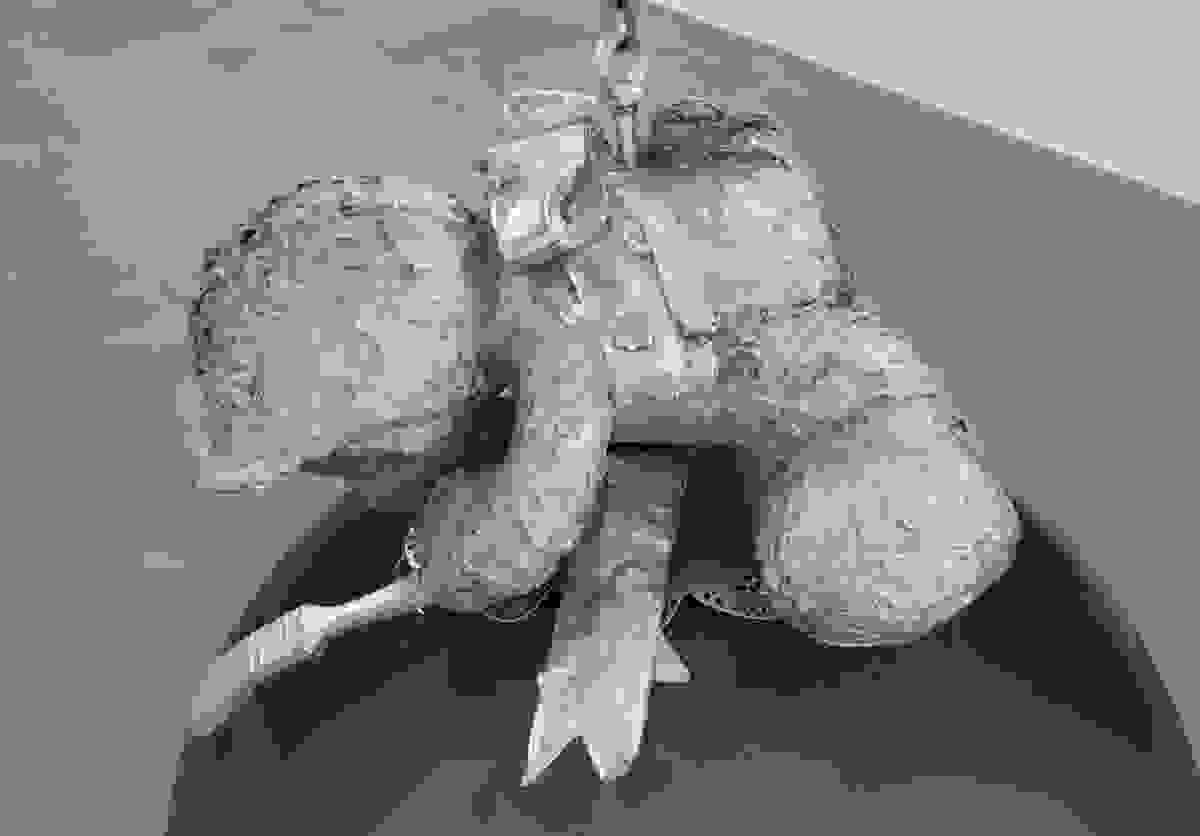

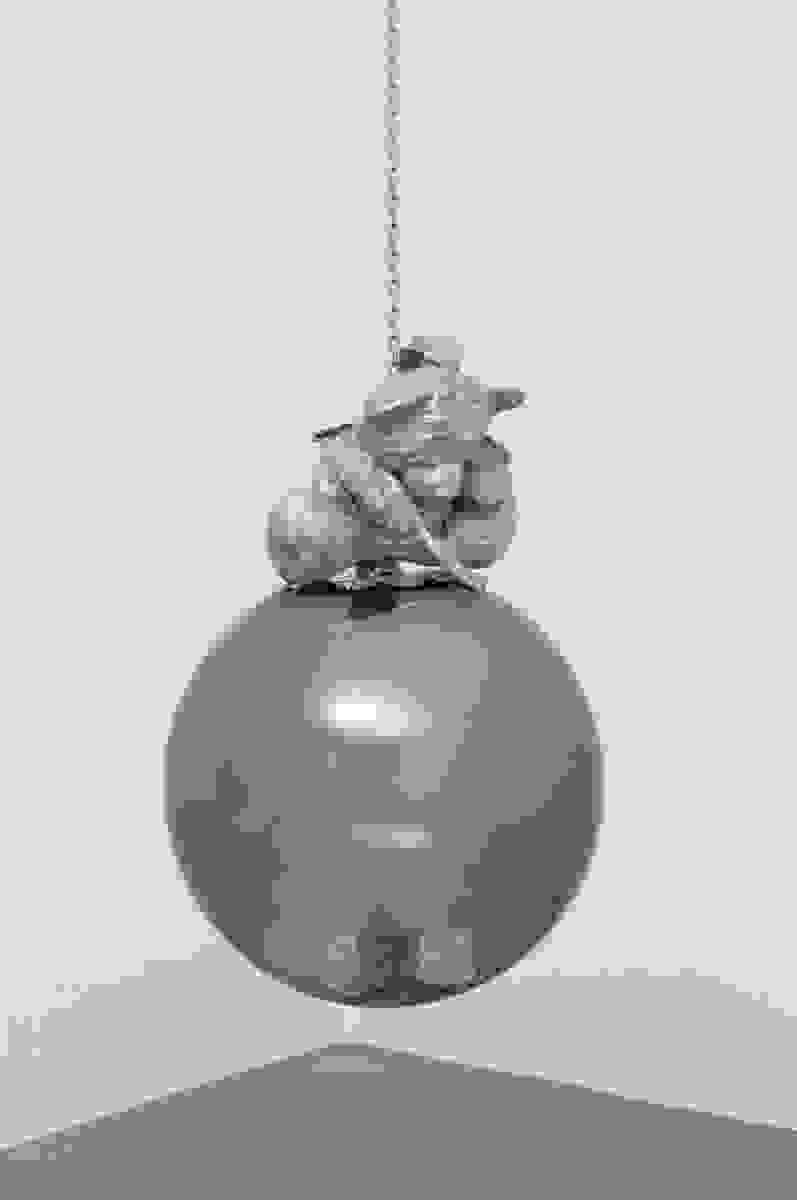

Guided by Dunkelberg’s own spectrum of affects –including, presumably, anger – the subsequent works in the exhibition can also be understood as a kind of impulse collage. In a poetic and flirtatiously affirming manner, with an approach similar to Woolf’s, she connects artistic fiction, personal experiences, and memories – both individual and collective – as well as (gender) clichés and symbolisms with contemplations specific to art and media. The result is a space of reference that is both symbolically and biographically charged, drawing on motifs such as hearts, teddy bears, bows, flowers, and (Christmas) baubles, and pointing beyond their inherent – alleged – cuteness and decorativeness.

While Woolf developed the intellectualised form of anger as a method of expression, using the figure of ‘the madwoman’ to reclaim patriarchal labels of the hysterical, crazy, and angry woman – the monster, the evil stepmother, the witch, and Medusa – Dunkelberg’s resistance lies in playing with contradictory attributions. Her madness, her anger, and her discord are reflected in the equally self-determined appropriation of the naivety, vulnerability, and sensitivity also attributed to women – in other words, the stylised weakening of the female subject. Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg’s perspective deliberately distances itself from generalities. Instead, she uses her subjective horizon of experience – her room of my own – to develop a personal and constructive approach that transforms proclaimed weaknesses into self-confidence and a distinct visionary language that challenges conventional attitudes. Powerful cuteness!

Text: Hendrike Nagel

Translation: Katerine Niedinger

Images: Andrea Rossetti