L‘Esprit Nouveau

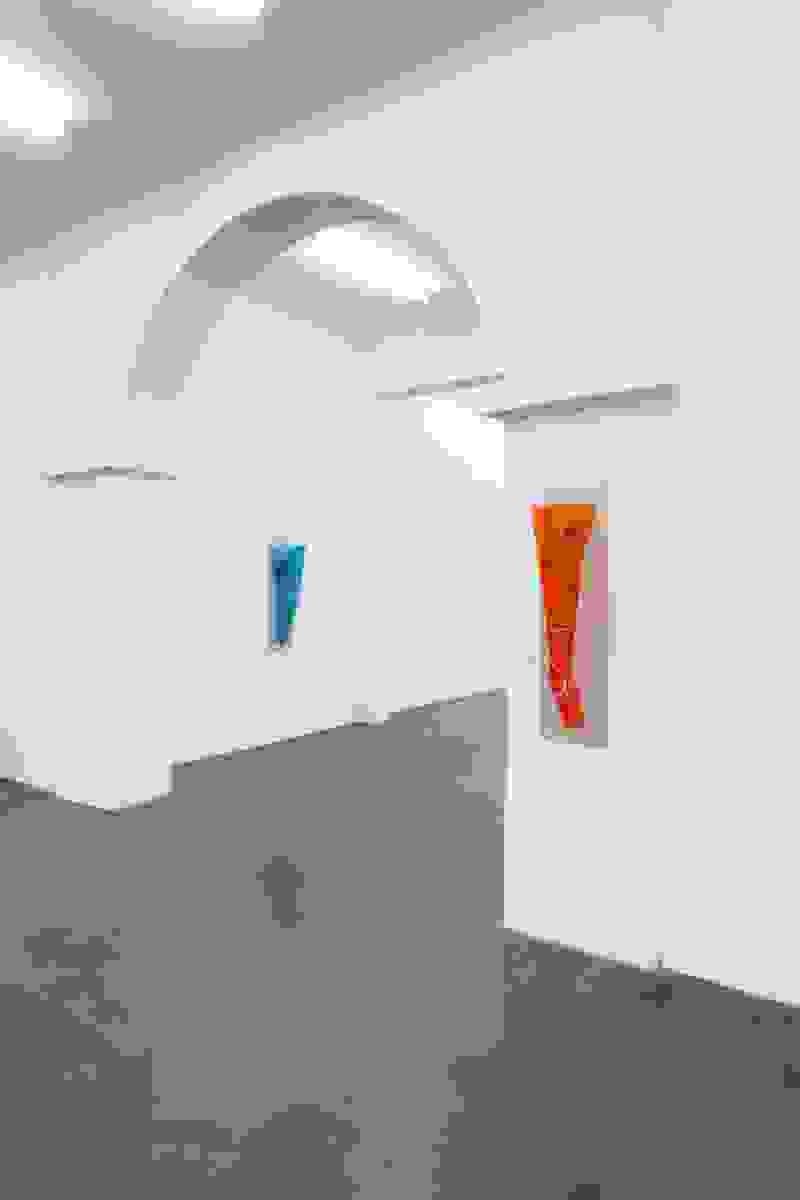

What you see is what you get

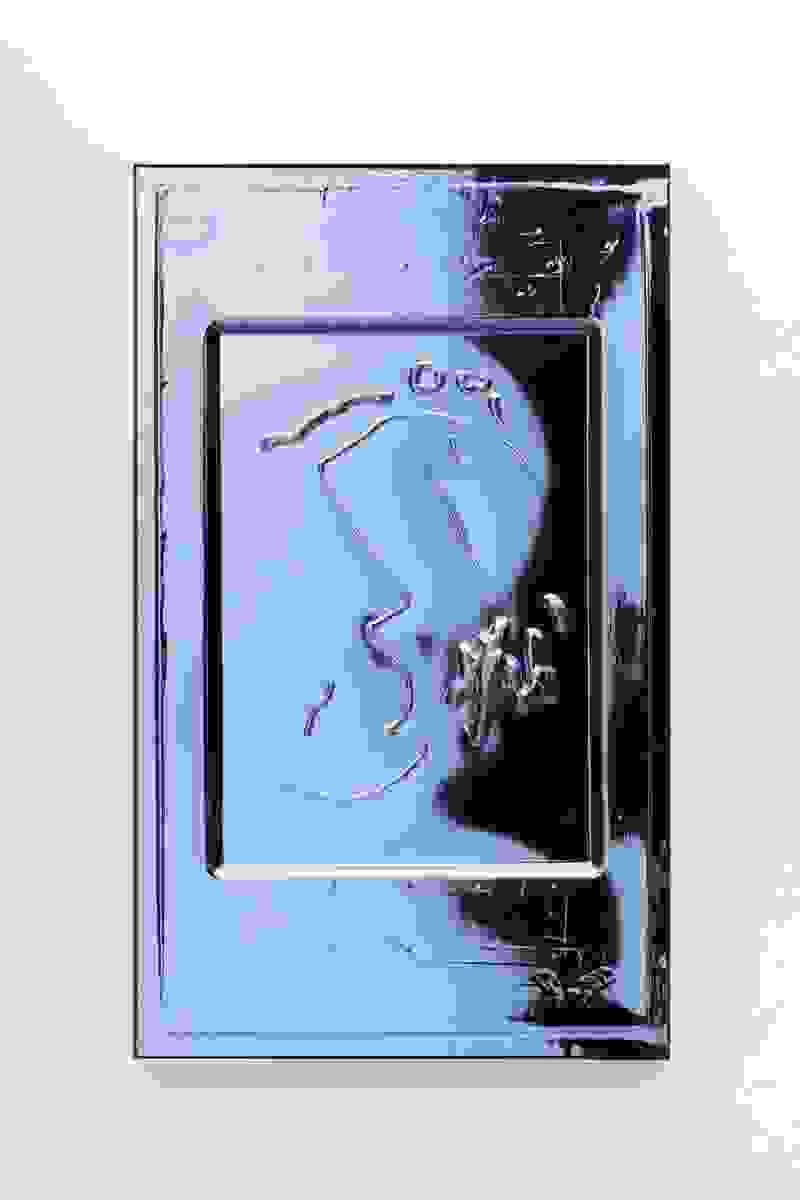

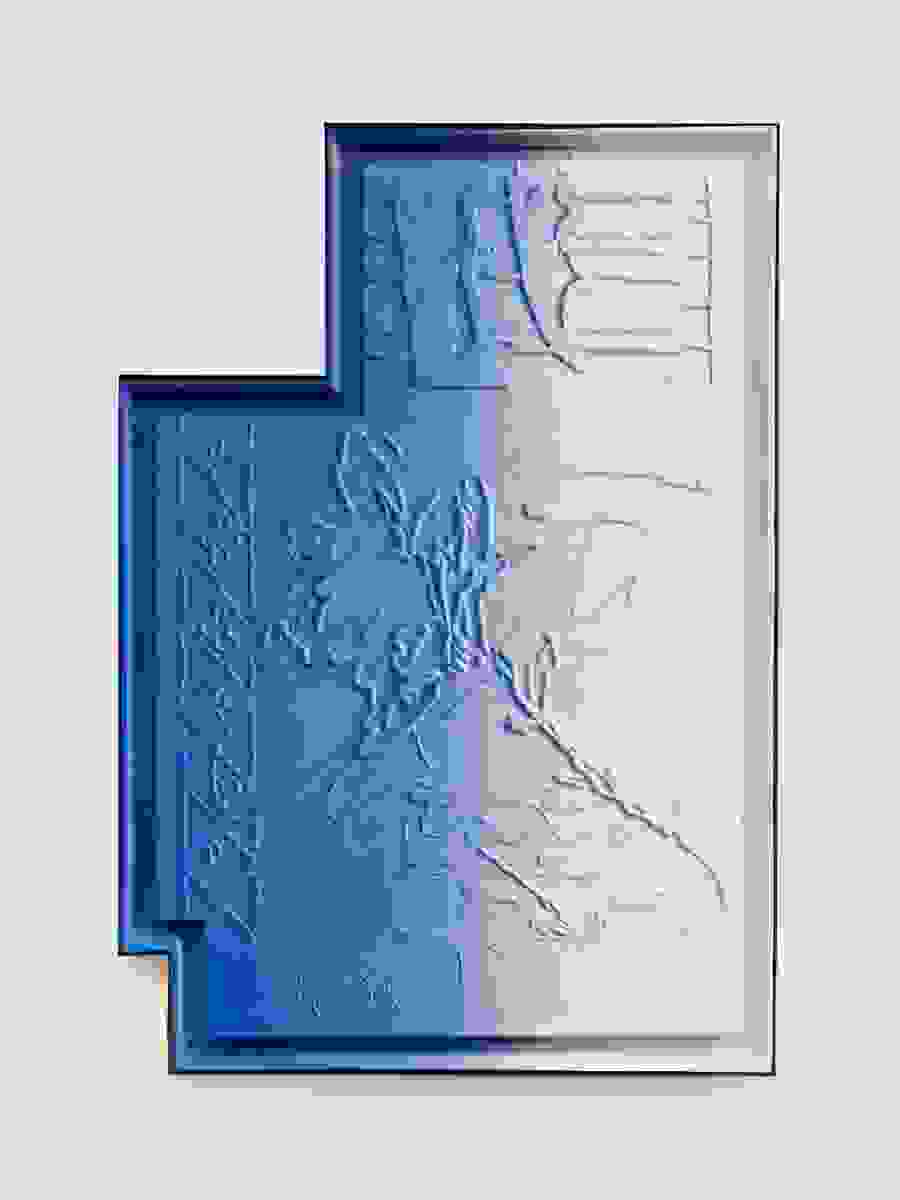

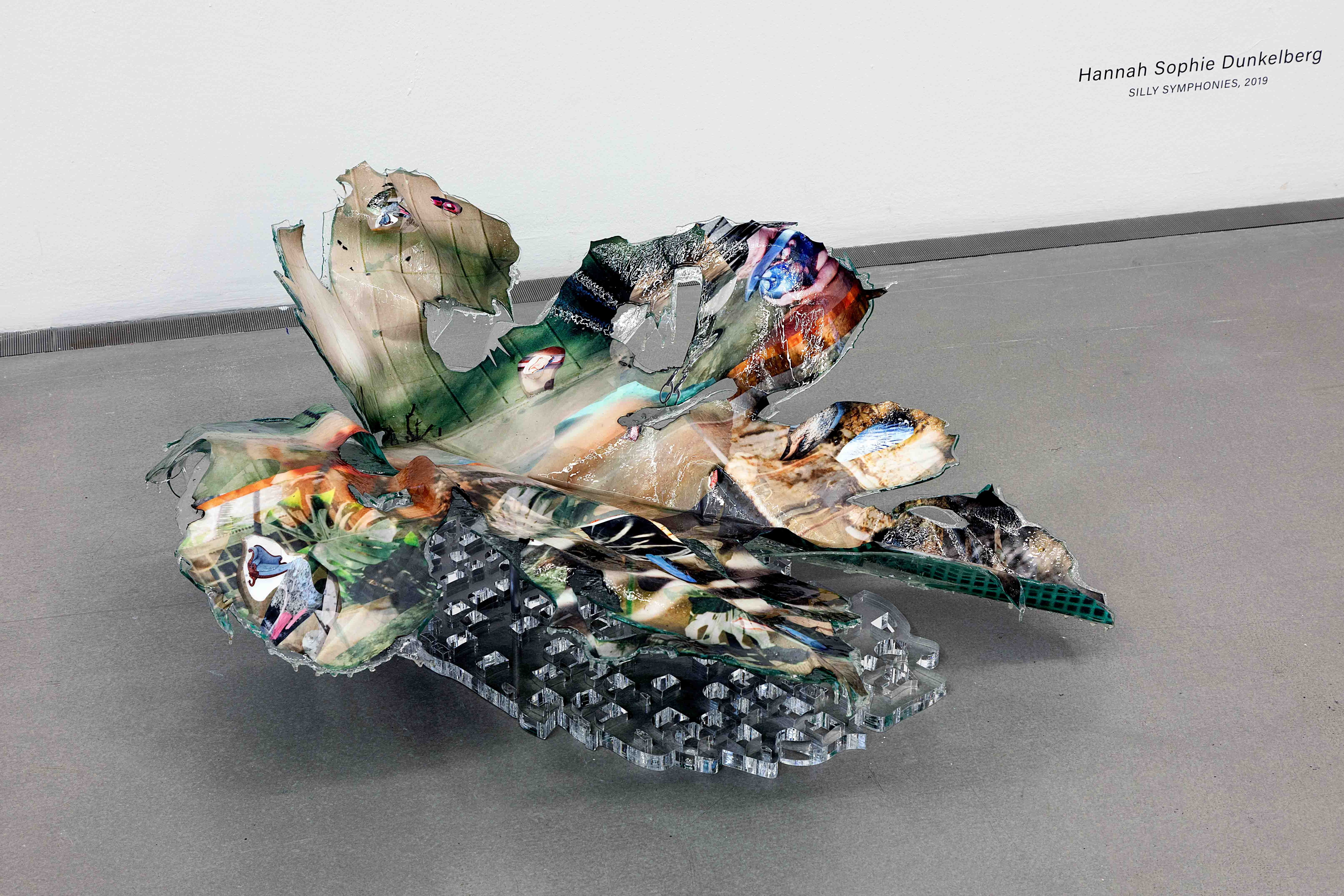

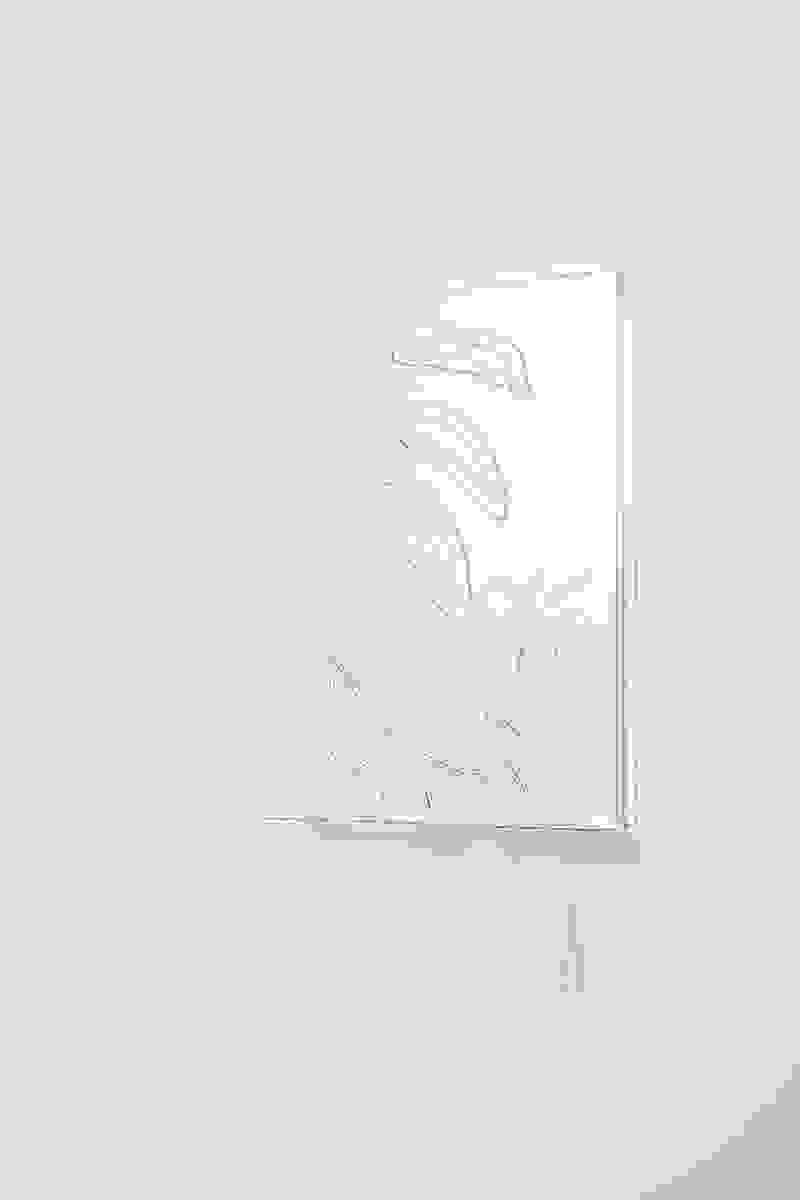

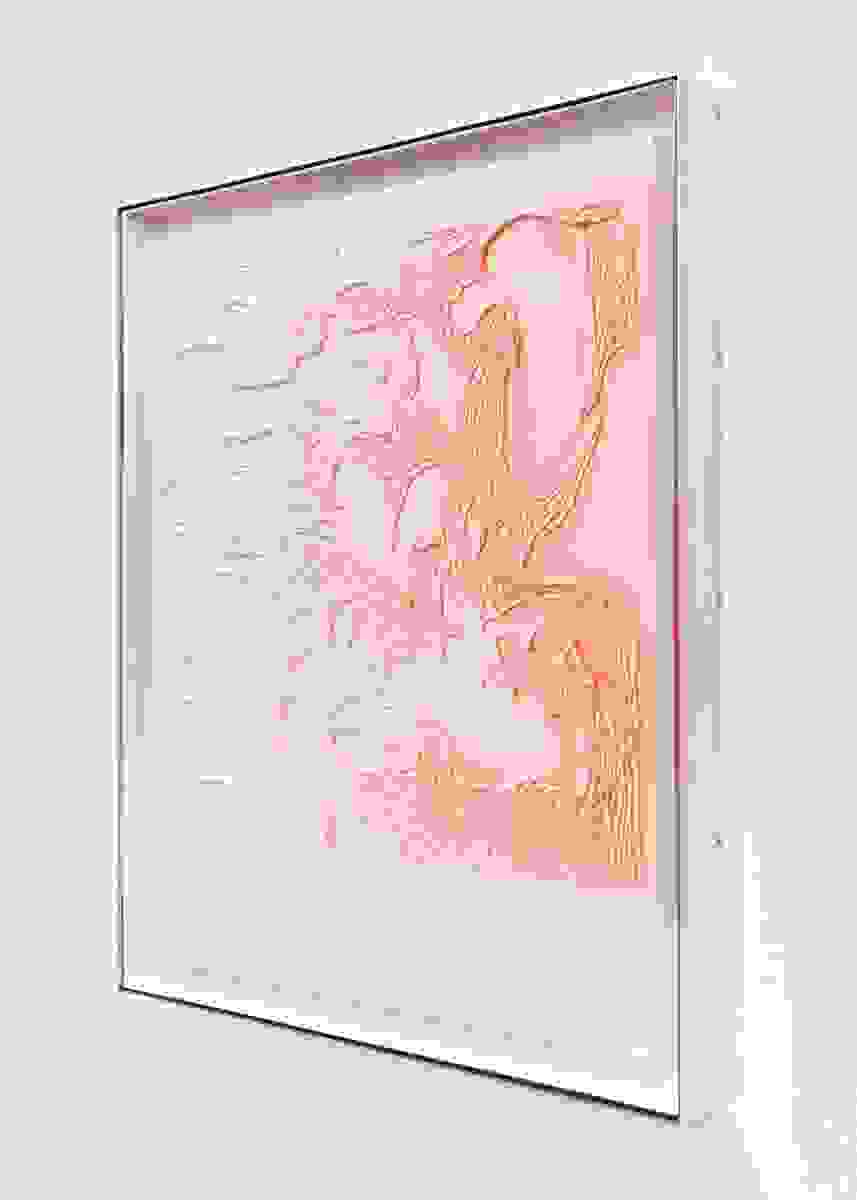

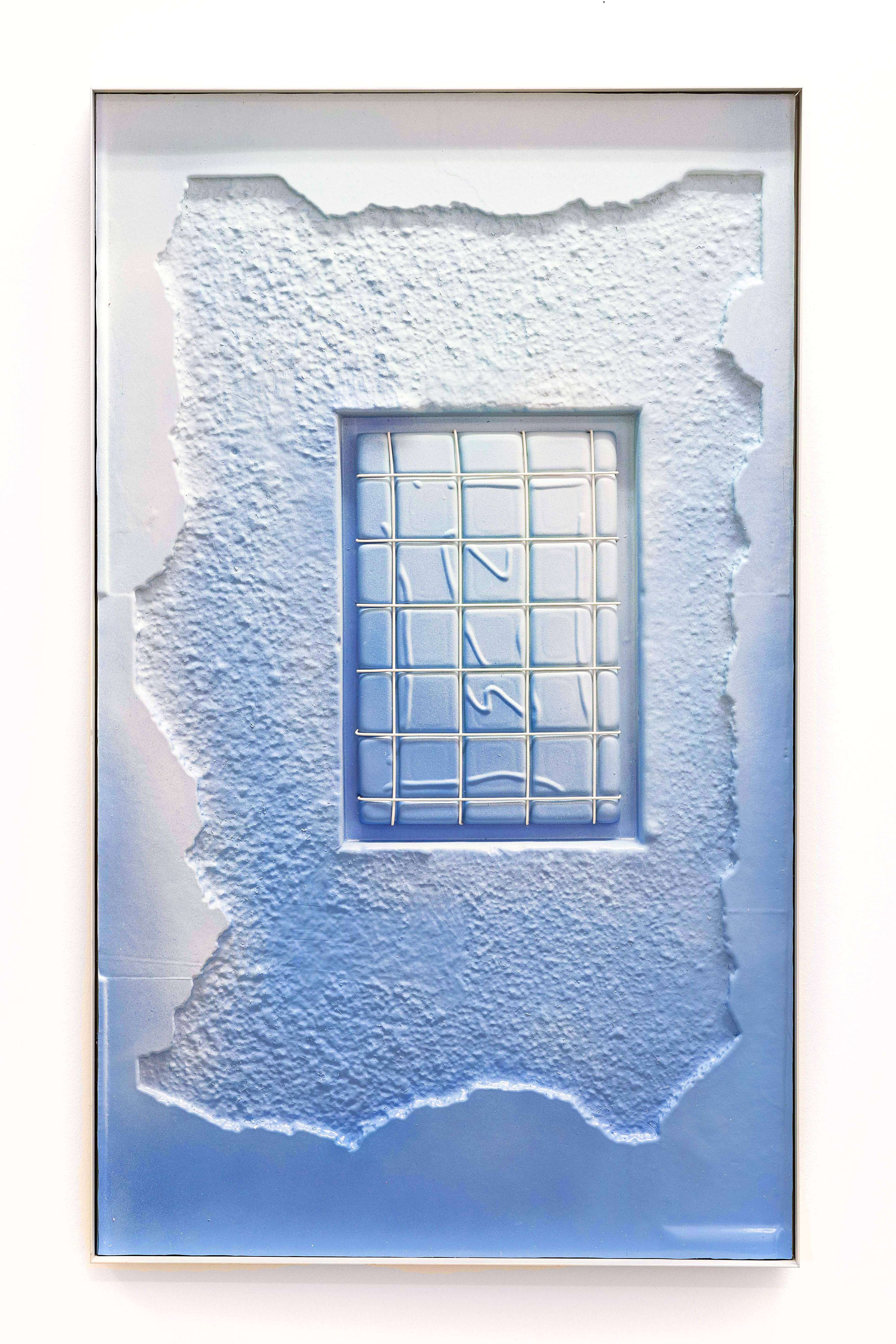

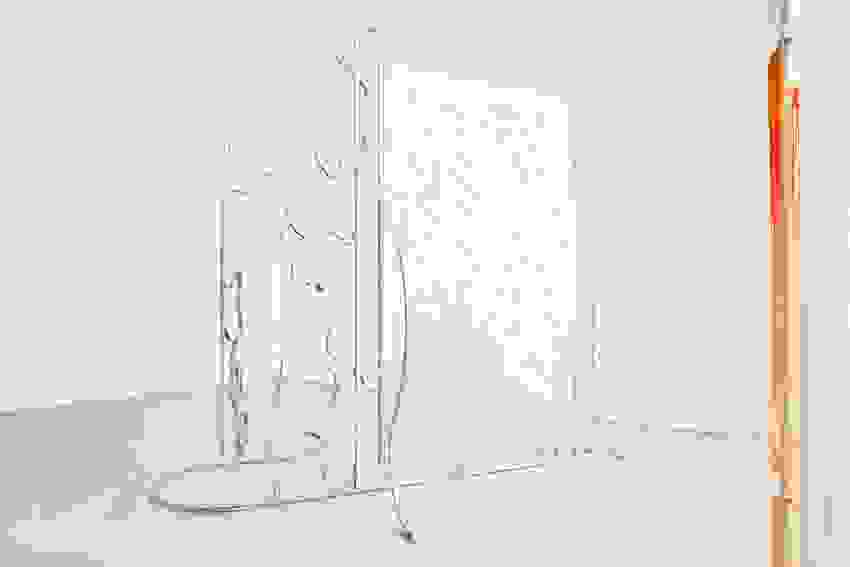

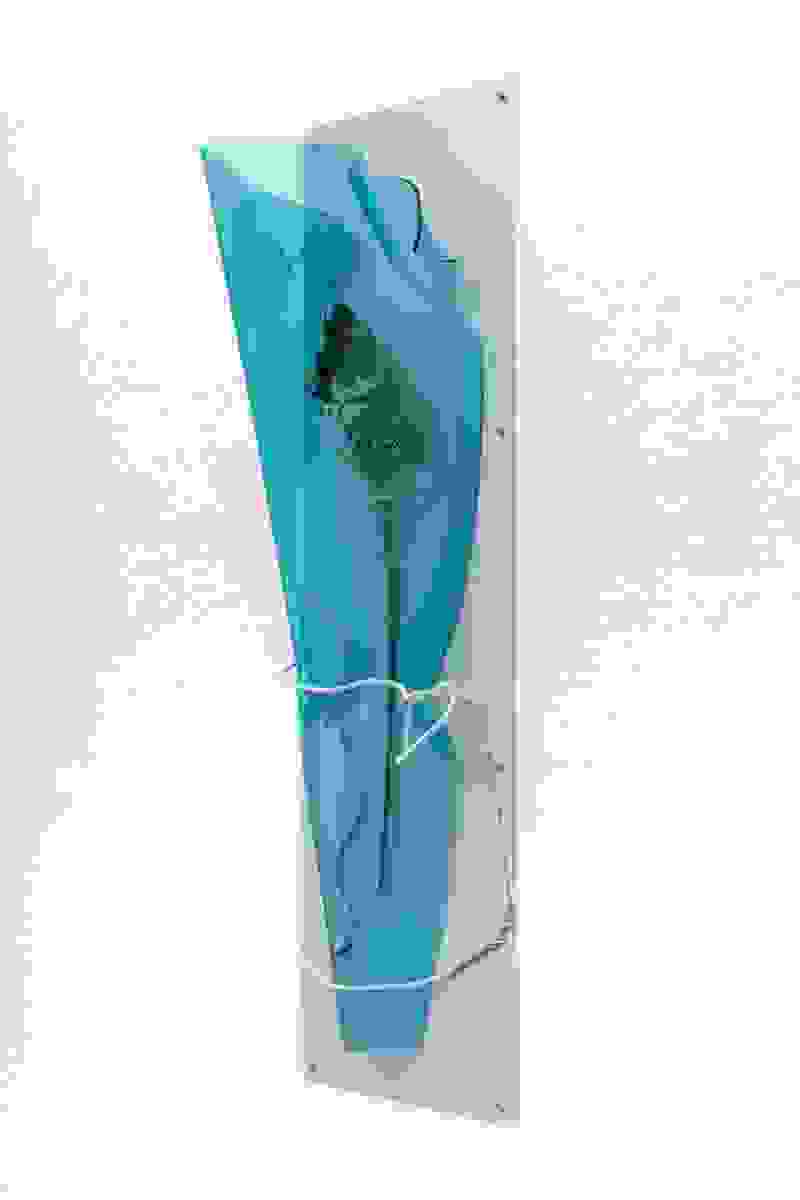

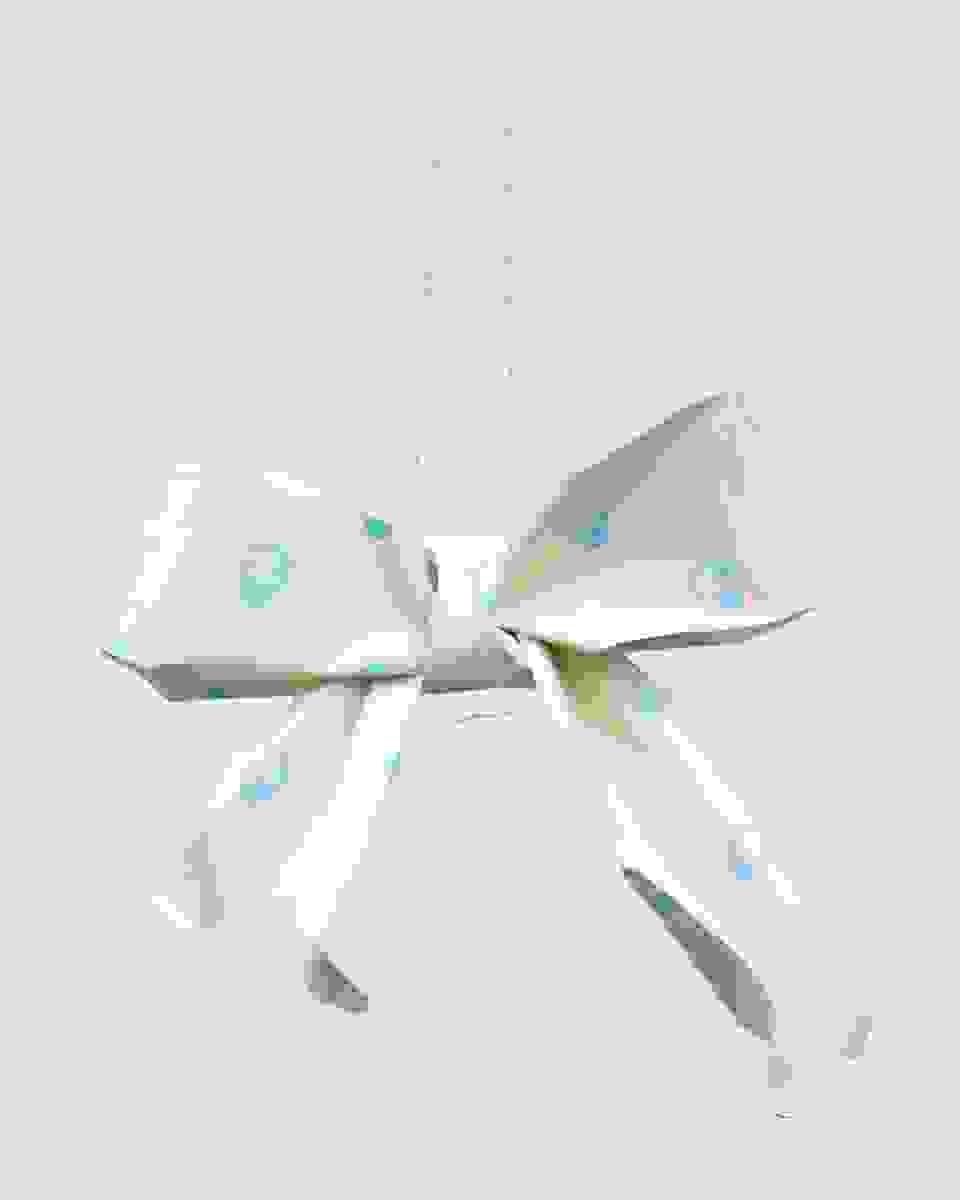

Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg’s artwork embodies a certain what ifness, taking the question as a stance. Like what if a painting were a sculpture? And vice versa? Or what if vaguely modernist and digital forms met in a mash-up of styles that knocked both from their pedestals? More tactically, Dunkelberg’s material process seems to be guided by what ifs, particularly in the idiosyncratic sequence of steps she developed to create her wall reliefs. Experimenting with the possibility of a mechanically-produced, inversion of her hand-drawn gesture, Dunkelberg designed a method that involves drawing, wood carving, industrial vacuum forming, plastic molding and car lacquering.

A sense of potentiality remains as palpable in the works as traces of their industriousness. Dunkelberg is hands-on in each step of her process and her work’s initial slickness reveals vestiges of production in bits of glue, impressions from machines or subtle screw marks.

While the Berlin-based and Bonn-born artist can be compellingly situated in a contemporary German context – say with regards to her former professor Manfred Pernice’s vivisections of the formal language of urban and domestic constructions or Jana Euler’s wry jabs at gendered German painting culture – it’s also worth reaching further afield to the Finish Fetish of 1960s Los Angeles to think through Dunkelberg’s seductive sheen. Artists associated with the movement adopted industrial fabrication processes and materials like plastic and enamel to create objects that brushed away boundaries between the handcrafted and machine-made, 2D and 3D and painting and sculpture. Craig Kauffman’s use of vacuum forming technology to make his plastic reliefs and Billy Al Bengston’s adoption of the auto body workshop spray gun as a brush lend Dunkelberg’s material experimentation a West Coast origin story. But she has no hang-up on an immaculate surface and is not after the pristine, taking such a fetish instead as something to poke holes in by (almost) literally doing just that. Where the aforementioned Macho men sought to do away with gesture, Dunkelberg stages a story of its persistence as the line derived from her freehand sketches rises to the surface of her reliefs, like lines of braille or covered tunnels grooved by ants. The scribbles and squiggles themselves occasionally resemble plants or architecture, others verge on decorative patterns or strange hieroglyphics rendered with the quality of line of a finger swiping a screen.

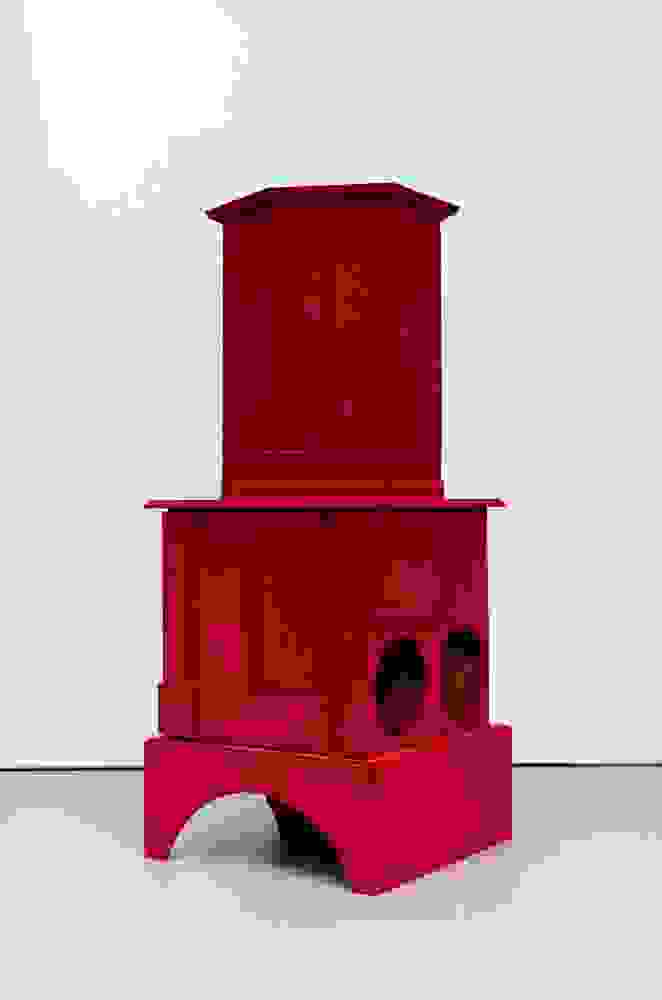

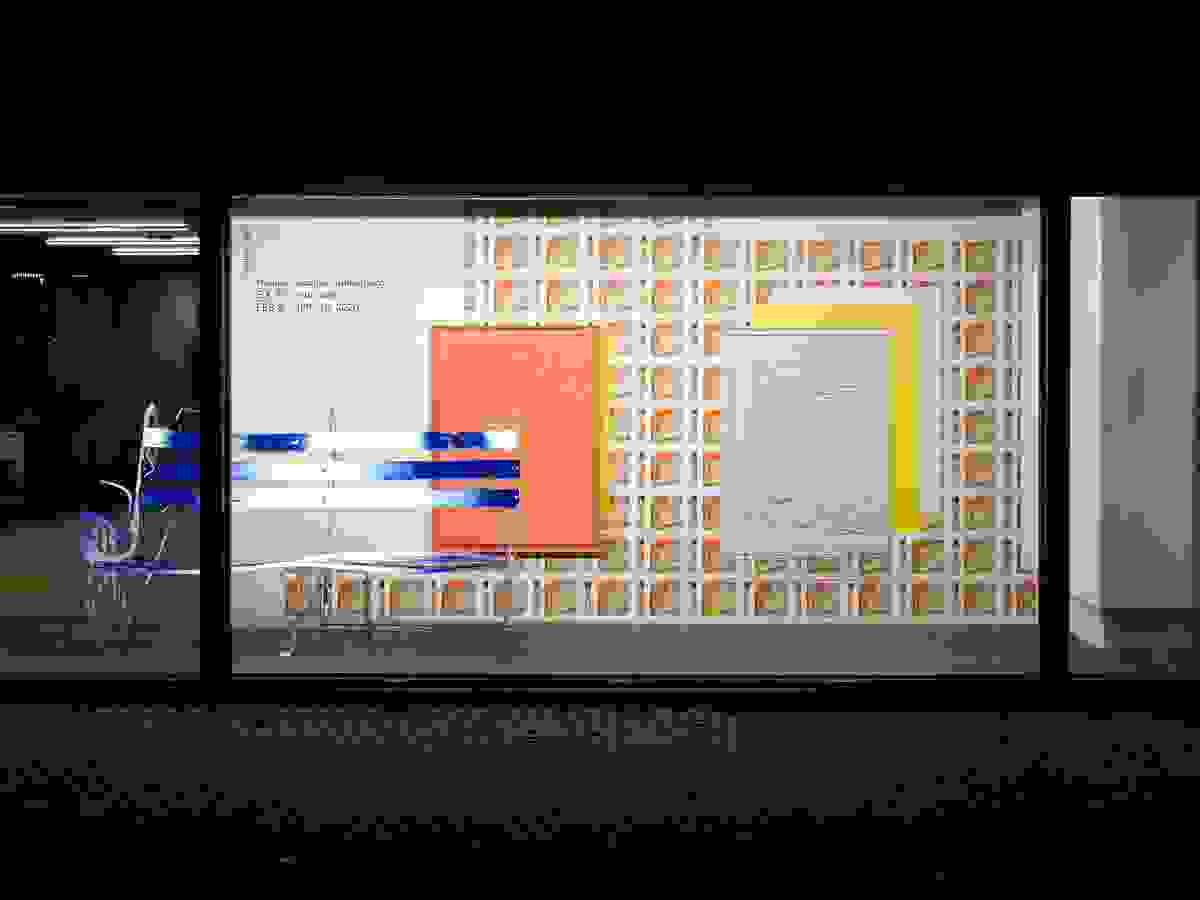

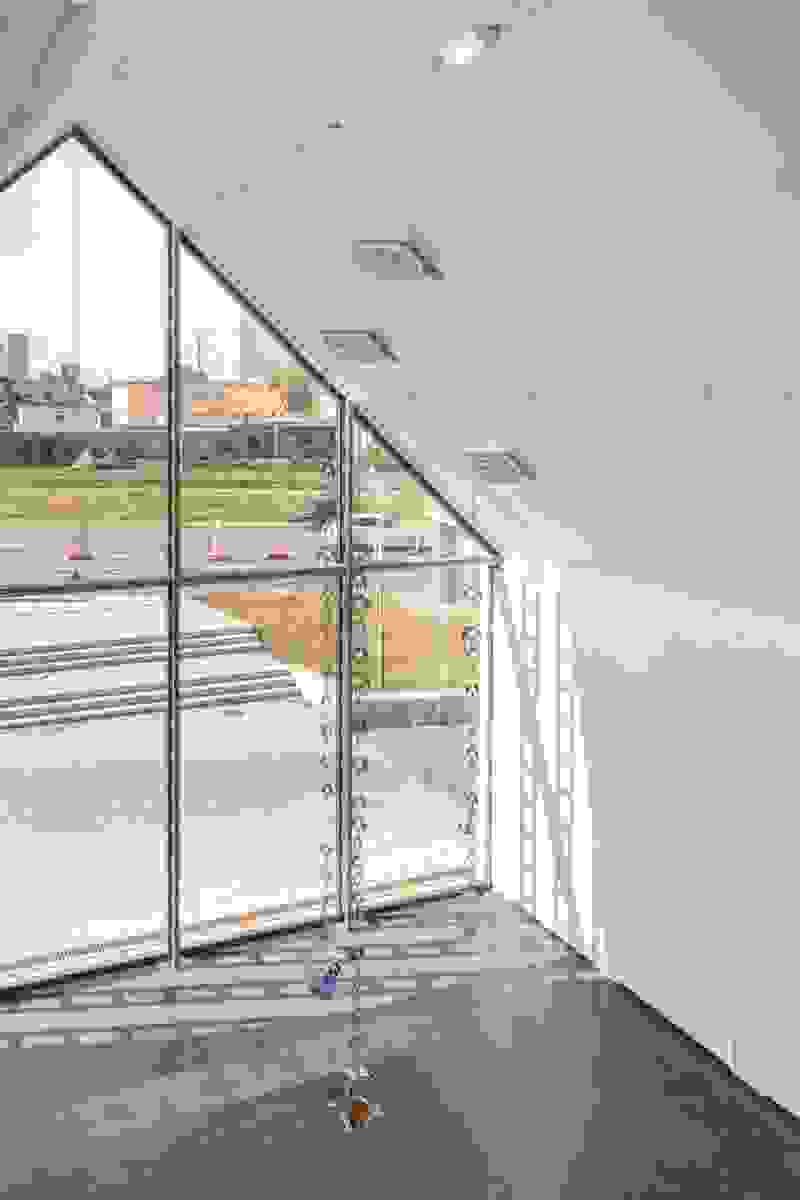

Attuned to the art historical pendulum between gesture and its promise of immediacy on the one hand and the desire for erasure of authorship and its hang-ups on the other, Dunkelberg also taps into a parallel tension between artificiality and authenticity. Such a dynamic is omnipresent in Potsdam, a suburb that holds tightly to its claim to fame as the former summer home of Frederick the Great, but is looser with its mashup of ornate architectural styles from throughout the ages. Against that parade of fake facades, her exhibition L’Esprit Nouveau, at the Kunstraum Potsdam, takes stock of such monumental forms and asks if art is up to the task of throwing a wrench in the machine. That is – drawing attention to the physical forms that surround us (architecture, furniture, the barrage of brands and commodities), the cultural baggage they carry and a collective susceptibility to take this all as a given. Dunkelberg mimics recognisable forms – often vaguely Bourgeois domestic furnishings – and through a brilliant play with material, simultaneously reduces these forms to a suave superficiality and sets in motion a subtle process of transformation. In a series of ovens, for instance, she recreates the essential accessory of a carefully restored, early 20th century Altbau and covers it with a synthetic fiber that conjures hazy associations: is this what Furbys were made of? Or those little dollhouse cat people? In any case, it’s delightfully weird. It’s like it’s all connotation, all fuzzy memory, all surface. Like there is no there, there.

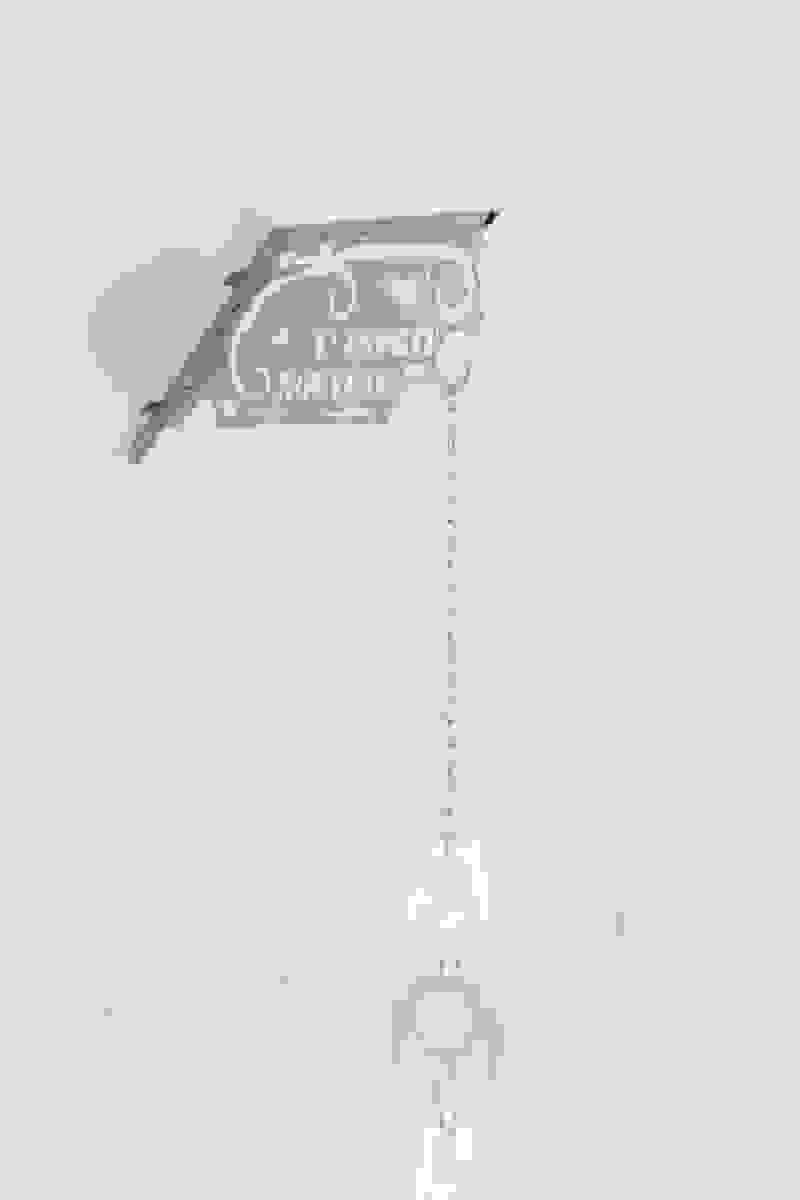

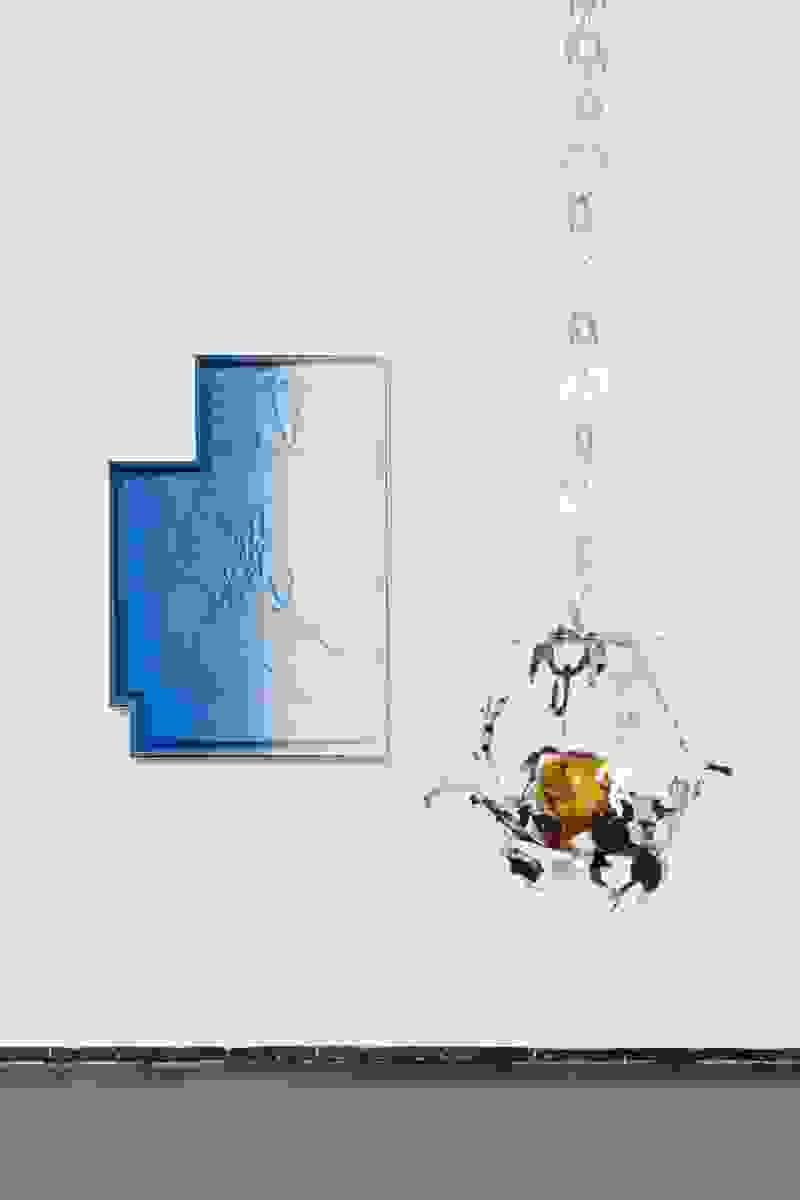

Constructed from interlocking metal rings that look like a cross between handcuffs and a botched sketch of something ornate, a series of lamp sculptures make a similar gesture. Despite the way in which they dangle in space, their physical heft and craggy lines, there is an illusion of flatness about these jagged chandeliers. And as such, a sense in which they are all about surface: shiny, luminous. These lamps also bear a striking resemblance to Giacometti’s lamps that hang at the Kronenhalle bar in Zurich; and it’s perhaps no surprise that driven by her own material experimentation, Dunkelberg inadvertently crafted something in the lineage of this master of sculpture as a process of reduction. But while distilling or paring down is also at the core of Dunkelberg’s practice, it’s in a wholly different vein. It’s cheekier, for one. And willing to ask, what if, what you see is what you get?

— Camila McHugh